|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

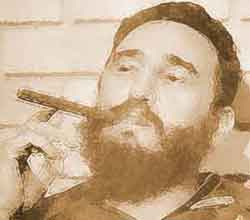

Alan Davis Alan DavisMostly Musk We were defectors from the American Dream. "Son," Papa said, scratching his bushy white beard, "I was cited for my work in the market and the big baloney punks couldn't take it, so it's off to Cuba. Nixon is a crook. Better Castro." He wasn't cited, I learned later, he was indicted, and it wasn't the stock market, it was something entirely different , but living in Louisiana, in certain essential ways, isn't all that different from living in Cuba. Havana, New Orleans, what's the difference? Castro, Nixon, or the current what's-his-name: what's the difference? Either way, they give you the shaft. "Good teeth," my mother said, gritting her own. "That's a big difference, Papa. If it's Cuba you need, it's Cuba you get, but you better find us a good dentist." "Teeth?" my father said, daunted, stroking his beard, and I laughed a big, greasy, sarcastic Papa-laugh, which made Mum glare, but he promised on the Bible, the one that he didn't believe in, to get us a good dentist, and so off we went to Cuba, by a circuitous route that I was too young to fathom. We were surrounded by sugar cane, just like in Louisiana, and by the carnal lilt of Spanish that seemed exactly the same to me as Cajun French, because I couldn't understand either one, except that Castro's bearded leather face smiled from every billboard. "That big cigar," my father said. "Those rotten teeth," said my mother. I thought Castro was Him, the one who beat back evil so Papa could be safe, but those bad teeth horrified Mum, who did not scare easy. My many brothers and sisters saw nothing wrong with the teeth, as big as buildings on the billboard. "They white, they white, they white teeth," we chimed, which made my mother beet red. "I will not permit a single member of my family to have even a single rotten tooth, because it would be un-American." "All right, Mother," my father said. He knew how stubborn she could be about the most trivial thing if he tried to bully her. I was way too young to hear the fight bell clang or to know what the fuss was really about, but my father arranged, somehow‹don't ask me, since he was a defector and I was a tike‹maybe it was Gomez, a genial lieutenant who respected Papa and who may have been having an affair with Mum, but somehow he arranged for all of us to visit the dentist at Guantanamo, the American miliary base on the tip of the island, and to have our teeth fixed by an Alabama dentist called Dick. "Just call me Dick," he said, and pointed to the nametag stitched to his smock. He thought it was funny. His own teeth were enameled and pearly white, as though painted with glossy latex. I was scared to death of this Dick, but one of his technicians, a Louisiana redneck called Doucet, threatened to pull out my gums with a pair of pliers unless I agreed to sit still, so I craned back my neck and opened my mouth so wide that my jaws felt sore for a week. While this Dick poked around in my mouth with metal implements that looked and felt like ancient medieval torture devices, he played Francisco Replada, aka Compay Segundo, on his stereo system. It was music that I knew well, because my mother played it often in the ancient hacienda we called home, and I have to admit that this dentist, this Dick, had a certain rhythm when he worked on my teeth, and years later I think that maybe Mum, God bless her soul, had the affair with him and not with Gomez, who was stiff like a white man, not my mother's type, as white as she was despite the hot sun. This Dick had a female hygienist, a brown-haired woman with great legs. She could tango, could salsa, and did the rumba around my chair while she cleaned my teeth with a kind of paste that smelled like perfume and tasted like salsa. I don't remember a lot after that, because there was some kind of gas in the musk and I was feeling good, really good, I mean I was flying, if you know what I mean (and I think some of you do), and as Dick gyrated his paunch the size of a medicine ball against my hip and ground an acrylic inlay into the cavities that Mum had not been able to stop, I lay there gassed and laughing, my vagus nerve steaming and sending excitement to the deepest most secret part of my brain, I was almost crying I was laughing so hard, and I didn't know if I was laughing because I was crying or crying because I was laughing, it was that complicated, but this Dick, he stuck his implement inside my mouth and played with my teeth until he was satisfied, I mean, perfectly content. I mean, he had a thing for teeth, just like Mum, if you know what I mean, my pearly whites he called them, and we were in Cuba, man, and Rebilado, aka Compay Segundo, was singing "Chan Chan" over the stereo system: El carino que le tengoYo no lo puedo negar Se me sale la babita Yo no lo puedo evitar. This is how my mother translated it: (The love I have for you I cannot deny My mouth is watering I love those luscious teeth.) Cuba is a place many lifetimes removed from where I live today, and yet very much who I still am, even when the winter cold makes my teeth groan, and I can still see that fat dentist and his bad breath as he leans over me, man I was a kid, helpless, mouth open and bleeding, eyes bright like the light bulb when a camera flashes. This Dick finished me off and called to Doucet to untie me and I spat out a mouthful of blood and thought that I would never recover, but then the leggy hygienist danced into the room and squeezed some more musk into my mouth to cleanse and soothe my gums and the stuff tasted so good, it was the best thing I had ever had, that I forgot all about the pain. Meanwhile, my brothers and sisters came into the room, their teeth also cleaned and fixed. Each in turn opened wide a mouth so that big brother—that was me—could inspect the goods. Mum, happy to have had the run of the base PX, two-stepped into the clinic with a bagful of groceries in her hands. "A chan chan le daba pena," the dentist shouted. He dropped his implements on the government-issued linoleum floor. "Let's dance, baby!" How his big bottom shook! Even with his mustache and weight, he reminded me for a moment of a sleek seal doing the best he could out of his chosen element. The group of us—Dick the fat dentist, Doucet the Cajun redneck, my American Mum with her bag of goodies, the leggy hygienist dispensing her musk, my brothers and sisters, and me, myself, and I, little me, with pearly whites courtesy of Uncle Sam—danced the cha-cha out the door into the hot Cuban light. Someone poured us tall drinks from a pitcher of iced rum and Coke. Gomez escorted us hush-hush from the base while we sat quiet in the back of a truck covered with canvas and then we spilled out and sashayed down a bright boulevard under Castro's pearly whites, those teeth as big as stucco huts in a country where dirt-poor was not a bad word. I was proud to be an American in a place America officially hated, because I loved my country and I loved Cuba, both at the same time, and the politicians with their false boundaries had nothing to do with who I was, with who I am today, and I did the rumba in the streets with the hygienist, did the ballroom tango on the beach with my American Mum, did the conga with choleric Papa who didn't really know how to have a good time, danced with Doucet, with Gomez, with the Dick at the head of the line, with the Cubans who decided to join, every one on the beach holding to the hips of someone else, all of us twisting along under palm trees that swayed in the sun, and the sand was white, pearly white, and my brothers and sisters clapped to the beat of the conga drum and opened their mouths wide to all comers so that everyone could see their teeth, pearly whites gleaming like appetite and desire in the hot Cuban sun. |